I’m a hacker. I’ve been writing code since I was knee-high to a Commodore 64, and even today, there are few things more addictive to me than sitting down, putting on headphones and getting into The Zone. So naturally, I knew a lot about programming before I worked at my first startup. But now that I’ve worked at a few (and started my own) I’ve re-learned a few important lessons – mostly by making mistakes:

1. Before I did a Startup, I Knew that Code is Important

I’ve worked at a lot of different places now (both successful and otherwise) and there’s been one constant among the successes: the early code always looked like it was written by a bunch of drunken gibbons. This seems counterintuitive, but when you can barely keep up with growth, there’s isn’t time to pursue software perfection. Failing companies, on the other hand, have lots of time to polish their codebase.

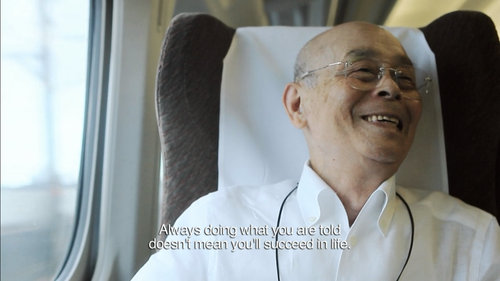

At one point in my life, I would have hated to hear this. But consider a metaphor: imagine that you’re a sushi chef. As part of your job, you have accumulated a fabulous set of knives. You’ve spent thousands of dolllars building your collection, and they’re a part of your competitive advantage as a chef.

But no matter how many hours a day you spend sharpening your knives, you are not a blacksmith. Your job is always to make sushi. You can have the best knives in the world, but if your sushi is bad and your customer service sucks, you’ll never succeed. You’re in the restaurant business.

So it is with software. When you’re running a company, you’re in the business of satisfying customers. Code is a tool that allows you to do that, but it is not an end unto itself. You can (and should) care about your code because it helps you serve your customers. But when you mistake the tools for the job, you’re headed for failure.

Lesson: Your customers don’t care about your test coverage, your technology stack, your version control system, or the algorithms you use. Your job is to solve your customers’ problems as expediently as possible.

2. …I Knew that I Should Care about Implementation, not Ideas.

This one sounds like it goes against conventional startup wisdom: launch fast! Execute! Iterate! Execution, not ideas! Fail faster!

Those are all great pieces of advice – as far as they go. But just because “ideas are worthless” doesn’t mean that you can fix a bad idea with great execution. And that turns out to be critical, because a bad implementation of a good idea beats the perfect implementation of a bad idea. Success is finding a good problem, and doing a good enough job of solving it.

A lot of programmers get trapped in the Improvement Death Spiral, spending their time building features or fixing bugs, in the belief that success is just One Feature Away. This is delusion. You only need to be good at solving one important problem, so it’s pointless to spend any time polishing a product unless you know that it’s solving a need.

A bad implementation of a good idea beats the perfect implementation of a bad idea.

How do you know that? There’s a clear litmus test: you won’t be able to hire fast enough keep up with the people who are asking you to improve your product.

Lesson: If you find yourself adding features to fix a failing product, you’d do better to ask yourself if you’re *solving a real problem, instead.*

3. …that Code is for Computers

This one is a stubborn myth. It seems that no matter how many times programmers are stymied by the poor documentation and communication habits of their peers, the conclusion they reach is that, programmers are just inherently bad at those things, and therefore, they shouldn’t be doing them.

That’s wrong. Wrong and broken.

If you’re part of a team, the single biggest impediment to your collective productivity is communication – it is, quite literally, an O(n^2) problem facing your team. And if code is your primary output, then you need to change the way you think about programming: code is for people. It just happens to run on a computer.

Too often, I see programmers spend hours writing code, then neglect the ten minutes it would take to update that code’s documentation. It’s as they’re saying “my time is worth more than the time of the dozens of other people who will maintain this code in the future.”. Considered in that light, it’s ridiculous.

Lesson: code is for people. If it isn’t documented, it isn’t done.

4. …that Writing Code is the Last Step.

Once you’ve written that feature and tossed it over the wall into production, you’re done, right? Wrong. Every feature has a lifetime. The code you write today, if successful, will live for generations of programmers after you. Entire teams might form, just to care for the code you’re writing today.

Think about that for a second. Entire teams of people might be working on your code someday. Do you care about them?

The point is not to paralyze you with fear of the future; the point is that code doesn’t end when you’re done writing the first version. In a very real sense, you are transferring a burden to your team. So make choices now that are respectful of their time: document, comment, organize. Curate.

Lesson: Respect the poor slob who has to maintain your mess. Someday it will be you.

5. …that a Programmer’s Job is to Write Code

Too many programmers think that the best use of their time is to sit down, slip on their headphones and crank out code. But when you consider that every line of code you write is something else that has to be maintained and supported over the product lifetime, the calculation changes.

When you’re writing hobby code, you can do whatever you like. That’s part of the joy of hobbies. But when you’re working on a product with a team, your primary obligation becomes maintaining the existing code. You’re a curator, not an artist. And you have other important jobs: coordination, communication, planning and mentoring. You’re being hired because you have a great big brain, and the best use of that brain is sometimes writing code…but often enough, there are more important things to do.

Lesson: a programmer’s job is solving problems. That doesn’t always require code.

You’re Not Just a Programmer: You’re a Product Manager.

You might be thinking to yourself: this stuff sounds like the job of a product manager, not a programmer. But If you’re writing code for a paycheck – especially at a startup – you are the product manager. If you care about your success, it’s essential that you think about your work as part of the big picture. It’s not just good for your startup, it’s good for your career.